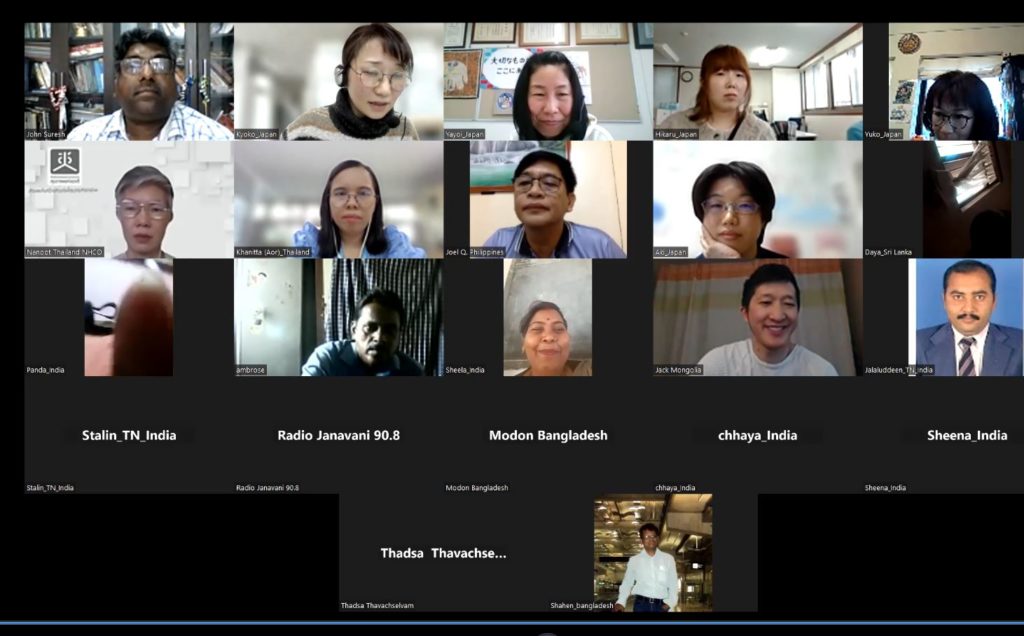

the 1st session of Health Assembly for social participation in Health Policy

Date: March 6th, 2024

Number of participants: 22

India: Stalin (ILDC 2019), Ambrose, Jalaluddeen, Karuppusamy (ILDC 2018), John (ILDC 2004), Chhaya (ILDC 2019), Vijaypal(Prayas), Panda (ILDC 2015), <Swapnil, Aamana, Sheela, Sheena (Health Equity Course-2023)>

Thailand: Khanitta (ILDC 2019), Nanoot Mongolia: Jack (ILDC 2021)

Nepal: Roshani(ILDC 1997) Sri Lanka: Thadsa (ILDC2023), Daya (ILDC 2004)

Philippines: Joel (ILDC 2000)

Brief report of the 1st session

Stalin shared about the Health Assembly (HA) in Tamil Nadu:

“The Tamil Nadu State HA was established in the 2021-2022 period. Block, Tulk, and District-level HAs began a year ago. The District HA is held once a year, and each of the Block, Tulk, and District-level HAs is a one-day program to discuss health issues in their communities. These issues include the unavailability and inaccessibility of health services in rural areas, the spread of cancer, and the unaffordability of health services. Local NGOs, Panchayat members, women self-help group (SHG) leaders, youth leaders, and village representatives participate in these discussions. The State HA, also held once a year, includes government officials and NGOs. However, government health personnel tend to dominate these assemblies, primarily focusing on improving health facilities and medical equipment, rather than addressing community health issues identified in local HAs.”

Khanitta inquired about the follow-up mechanism after the adoption of resolutions in the State and District HAs in Tamil Nadu.

Stalin responded, “We are unclear about not only the follow-up but also the entire mechanism for conducting HAs. The process of deciding the agenda is not transparent, as everything is set up by the government.”

Khanitta explained that in Thailand, a follow-up mechanism is in place as implementing resolutions takes considerable time. The follow-up process involves the government, academic institutions, and CSOs.

Khanitta noted, “The State HA in Tamil Nadu is similar to the National HA in Thailand, and the District HA in Tamil Nadu resembles the Provincial HAs in Thailand. However, there is a significant difference in the process: the National HA in Thailand is not a one-day event but an almost year-long process to discuss agendas and formulate relevant resolutions.“

Ambrose shared his observations on the HAs.

“The HA in Tamil Nadu is a good concept, but there is no concrete implementation plan. There remains a significant communication gap between the government and the community, as well as between government departments. There is no proper communication channel or measure from the government to the community, and vice versa.

Karuppusamy emphasized the importance of conducting research to provide evidence of coordination gaps in the HA. Without evidence, advocacy efforts are less effective.

Ambrose mentioned “We propose forming Community Health Facilitation Forums in each village. These forums, consisting of potential youth, women, and retired government health personnel, should be capacitated by NGOs to bring community health issues, especially challenges in accessing healthcare services, to the District HA. It will take 2-3 years to strengthen this grassroots health movement, particularly among marginalized groups such as Dalits and tribal people.”

Nanoot asked about collaboration opportunities before organizing HAs.

Stalin responded that his organization has collaborated with the Rural Health Mission under the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) to operate mobile medical services for tribal communities since 2007. While the government’s support for NGOs’ efforts to promote social health and welfare schemes is welcomed, the HA, which involves bringing people’s issues to the government, is seen as a form of advocacy and rights-based activity, which is not acceptable to the government.

John commented, “While there are collaborative efforts between the government and NGOs, in reality, the government just takes advantage of NGOs.”

Nanoot noted, “This is the 17th year of the official HA, but there were 5-7 years of preparatory work before the official launch. The HA mechanism in Thailand was established step by step.”

Summary and Recommendations

Chhaya summarized the participants’ points, noting that the HA in Tamil Nadu is very bureaucratic, with little space for NGOs and community members to raise their issues. It is crucial for NGOs and communities not only to attend the HA but also to participate in planning, setting the agenda, organizing the HA, following-up on the implementation of the resolutions.

Nanoot suggested three points for the Tamil Nadu team:

- Study the gaps not only in the healthcare system but also in coordination between CSOs and the government, as well as between government departments. Identify whether the problems are due to leadership, structure, regulations, laws, or other factors.

- Explore solutions and strategies that are implementable at the local level, such as at the block level or in specific communities. Because the idea of the HA is co-creation, co-action, and co-benefit, it is essential to identify the benefits of the HA for the government, not just for NGOs and the community, to change the government’s attitude and mindset about the HA.

- The Thai model cannot be copied directly to Tamil Nadu. Instead, study and explore the best model suitable for the Tamil Nadu context in collaboration with People’s Health Movement (PHM) in Tamil Nadu, AHI, and its network members, including NHCO in Thailand.

Chhaya suggested that if the Thai team could share their preparation process and follow-up mechanism for the HA in Thailand, and explain how civil society engagement is ensured, it would be helpful for the Tamil Nadu team.

The participants of the session agreed that the next session would focus on these points.

- Categories

- Uncategorized

One thought on “the 1st session of Health Assembly for social participation in Health Policy”

Comments are closed.